Forgotten Places of Colombia

Bogotá

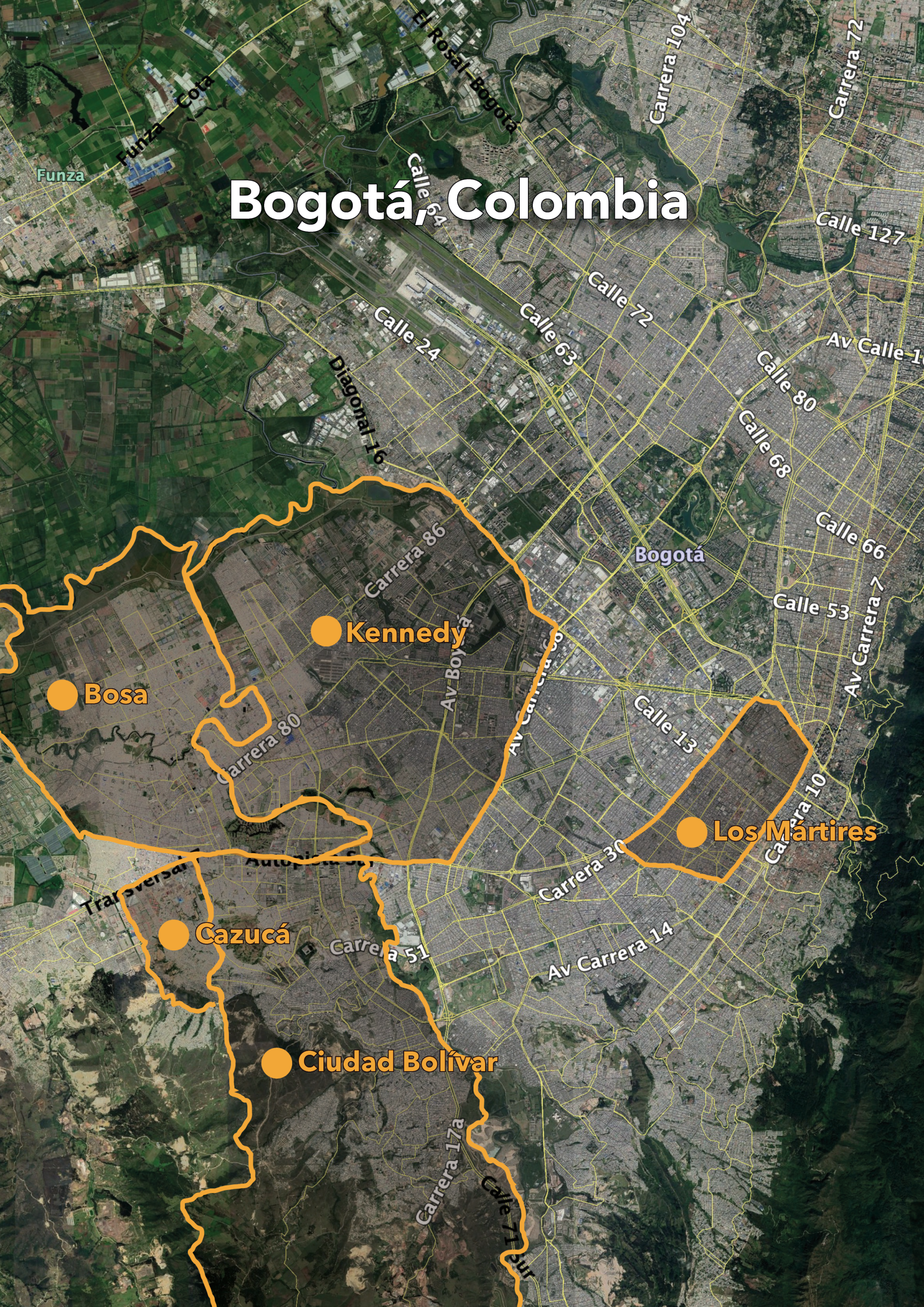

Bogotá is Colombia's capital city and with over 12 million inhabitants its largest city. The Bogotános are called 'Rolos', but Bogotá is inhabited by people all over Colombia. Because it is Colombia's capital city, many move to the city looking for work. But it is also the destination of thousands of displaced people that had to flee their home due to the violent conflict or poverty. The city does not have enough work for all those who arrive, nor is it able to provide everyone with proper housing. Therefore many settle in the outskirts of the city, building their own houses on the high hills of the city of gold. The informal settlements stretch over into Bogotá's neighbour municipality Soacha. Soacha however, has even less recourses to help the new arrivals, and without government presence, there is a lack of almost everything: education, healthcare, proper housing, job opportunities, and safety. In general Bogotá can be divided in two: the rich north and the poor south. The two generally don't mix. In the middle lies Los Mártires. Read more about both areas below.

Los Mártires

Los Mártires is one of the poorest areas in downtown Bogotá. It is ill-reputed for its drug consumption, micro-trafficking, prostitution and homeless people. It was home of the notorious neighbourhood named La L. This tiny neighbourhood, also called El Bronx, used to be the center of micro trafficking and drug consumption. For there was no other place to go, many of the homeless found a home in this neighbourhood, until the government decided to evacuate the entire area in 2016. Now, the neighbourhood is transformed into a creative district named El Distrito Creativo El Bronx. While the crime left El Bronx, it didn’t leave the city, and the homeless remain homeless elsewhere in Los Mártires, left to their own fate, with little to no help. People from this area are often either born or forced into these circumstances and are raised in extreme poverty surrounded by drug dealers and consumers. With little opportunities many of them follow their example. This has created an enormous stigma on people from this area, making it even harder for them to receive help or to find work.

Read more about 'La L', also known as 'El Bronx', by clicking on the link below.

Cazucá, Ciudad Bolivar, Bosa, Kennedy

Moving towards the outskirts of Bogotá we find long-stretching informal settlements built on the hillsides of the city. Bogotá’s biggest slum is called Ciudad Bolivar which unnoticeably changes into Cazucá on top of the hill, on which lies the border between Bogotá and its extremely poor southern neighbour Soacha. The slums are home to millions of people who moved to the city in quest work or as refugees from the ongoing conflict in Colombia and more recently in Venezuela. Among the other slums are Kenndy and Bosa. People in these slums are often dubbed displaced, and they live in self-made houses, which is often informal, hence, illegal. This means that their houses are not registered as being part of the city. There is a process called the legalisation of informal settlements, however, this doesn’t apply to much of the slums, as they are built on dangerous slopes, which are in high risk of landslides. Therefore the people are left to fend for themselves. Without government presence there exists a power vacuum that is filled by gangs and paramilitaries that bring violence and fear to the inhabitants. Anyone that compromises the power of the gangs risks his or her life, as many community leaders continue to get killed without any consequences for the killers, without any justice and often without even a short news article.

Sucre

If you have ever read Gabriel Garcia Marquez's ¨One Hundred Years of Solitude¨¨ike, you will understand Sucre. A department where magic, love, resilience and violence coexist as neighbours.

Sucre is a department located in the north of Colombia, in the Caribbean savannah, bordering the departments of Bolívar, Cordoba as well as the Caribbean Sea. This location has had strategic value during different moments in Colombia's history. During colonization it was an area where African slaves settled and later those who won their freedom. Therefore, a lot of Sucre´s culture is influenced by the African diaspora. Later, during the years of the civil war (1930-2000), different municipalities and townships of the department experienced the conflict directly, as it was a strategic passage for weapons, drugs and military forces. Its quick and easy access to international waters facilitated drug trafficking and its vast jungle served as a refuge and hideout for illegal activities.

Due to the war and neglect by the state, Sucre is one of the 10 poorest departments in Colombia, with a

poverty index of 51.4. Therefore, there´re different municipalities and villages where there are no public services, medical centers, clean drinking water or even schools.

During our trip we were able to visit some of these places: Galleras, where the only source of water is a rainwater well, or Altos del Rosario where there are no public services and crime rates are skyrocketing. There are many other examples of places where the right to basic needs is violated. But despite this harsh reality, Sucre is a department that thanks to its inhabitants is full of culture, resilience and strength.

If you go to Sucre be sure to eat a Sancocho Trifasico or as Profe Lina calls it, the healing Sancocho (soup), listen to the sound of the traditional gaitas, drink a Borojo juice for to increase your strength, and dance to Champeta music that blasts from the speakers on many street corners.

Sucre still needs a lot, but if there is one thing it has plenty of, it´s love, flavor and joy.

Read more about our project in Sucre by clicking on the link below:

Medellín

For millions of people, the first person they think about when they hear about the city of Medellín is Pablo Escobar. The city was infamously branded the most dangerous city in the world, during Escobar’s ruling. In recent decades however, the city has gone through a tremendous transformation, bringing the murder-rate down dramatically and making it one of Colombia’s safest big cities. This transformation was produced by ambitious municipal interventions such as the construction of a cable car system, connecting the poorer areas up the hills with downtown Medellín. But most of all, it was the people of Medellín that decided to change the fate of their city once and for all. In Comuna 13 for example, art has become the vehicle of social change, taking kids out of the hands of the drug cartels and offering a different future, without violence, without drugs and without poverty. However, Escobar’s legacy lives on through the stigma that he imposed on the city's name and its people. Now it is time for the people of Medellín to reclaim their city and its name, by showing the world what the city is really about.

Chocó and the Pacific Coast

Chocó is Colombia’s poorest department. Together with other departments on the Pacific coast it is home to Colombia’s largest population of Afro-Colombians. They have suffered and are still suffering massively from Colombia’s conflict, being in the middle of the violence caused by guerrillas, paramilitaries, drug cartels and the government. For the same reason tourists have largely stayed away from these areas and so has their story remained largely untold. Poverty in Chocó is severe, and many people therefore move to the city in search of a better life. However, at the same time the entire Pacific coast has an extremely rich natural and cultural heritage, which is ignored by society, even in Colombia itself.

Cartagena

Cartagena is named the #1 destination of Colombia in the Lonely Planet. It has therefore become an increasingly popular destination for tourists and real estate developers, and rich foreigners have practically bought up the walled Old Town and the modern peninsula called Boca Grande on which many fancy hotels have been constructed in the last decades. The influx of foreign money has caused incredible gentrification, a skyrocketing of property value, and consequently displacement of the poorer locals. At the same time, Cartagena has been, and continues to be, a location for many displaced Colombians that have fled their hometowns due to violent conflict or pressing poverty. These people do not benefit from Cartagena economic boom, as can be witnessed by anyone taking the bus from Cartagena towards the port-city of Barranquilla. We believe that tourism can be a good thing for the locals as well as the visitors. However, it is important for tourists to understand the living situation of the people living in the places they visit. Right now, they are pretty much invisible to the average tourist. That is where we can make a change. We can let the current and future tourists know more about the inhumane circumstances many locals endure, for them to possibly find ways to help out.

San Andrés

San Andrés is an island located in the Caribbean Sea, not far from Nicaragua. Recently, the island has been hit by a hurricane, which has left many people without a roof. We believe our work can be helpful in these situations, as people depend on donations and governmental help, which often falls short as they lack visibility. With our projects we can increase their visibility, and show the world the humanity of the people living in these disaster-struck areas, for them to get up and help out financially or otherwise.

La Guajira

La Guajira is the second poorest department of Colombia. Lying on the north-coast, bordering Venezuela, it is home to the Wayuu people, that have inhabited the department for many centuries. They are known for their beautiful handbags, that are sold all over Colombia in tourist shops. However, at the same time they suffer from extreme famine and draught. La Guajira is for a large part controlled by oil and coal companies that have dried up the river to make way for their own business, leaving the locals without any water. They are ignored, silenced and left to starve to death.