About Colombia

A Two-Sided Development

“Having largely overcome the instability and violence that has blighted it since the mid-20th century, Colombia is currently one of the most dynamic and fastest-growing economies in Latin America. (…) Having avoided the recessions that have hit many Latin American countries in recent years, Colombia looks set to continue growth at an impressive pace in the near future” (Lonely Planet, 2015: 284).

A Violent Past

Gary Leech points out that “while Colombia’s history resembles that of other Latin American nations in many ways, there are some unique aspects to the country that have impacted it politically, socially and economically” (Leech, 2011: 4). For instance:

“Unlike in any other Latin America country, Colombia’s principal cities – Bogotá, Medellín, Cali and Branquilla – are separated from each other by vast expanses of towering mountain peaks and dense, lowland tropical jungles. Many of Colombia’s provincial regions developed in relative isolation from the capital, Bogotá. Prior to the twentieth century, it took less time to travel from the Caribbean port city of Cartagena across the Atlantic Ocean to Paris than to the nation’s capital – seated on a savannah 8,600 feet up in the Andes mountains” (Ibid).

Due to this geographical isolation, the Colombia government located in Bogotá, never fully controlled all of Colombian territory (Leech, 2011: 5). When rural populations did occasionally have to deal with the government, this often came with violent repression (Ibid.) Scholars Villar and Cottle point out that unlike other Latin American countries, Colombia has remained “deeply divided geographically and politically”: “Following the Wars of Independence from Spain, Colombia experienced fourteen civil wars, numerous peasant uprisings, two wars with neighbouring Ecuador, and three coups d’état” (2011: 18).

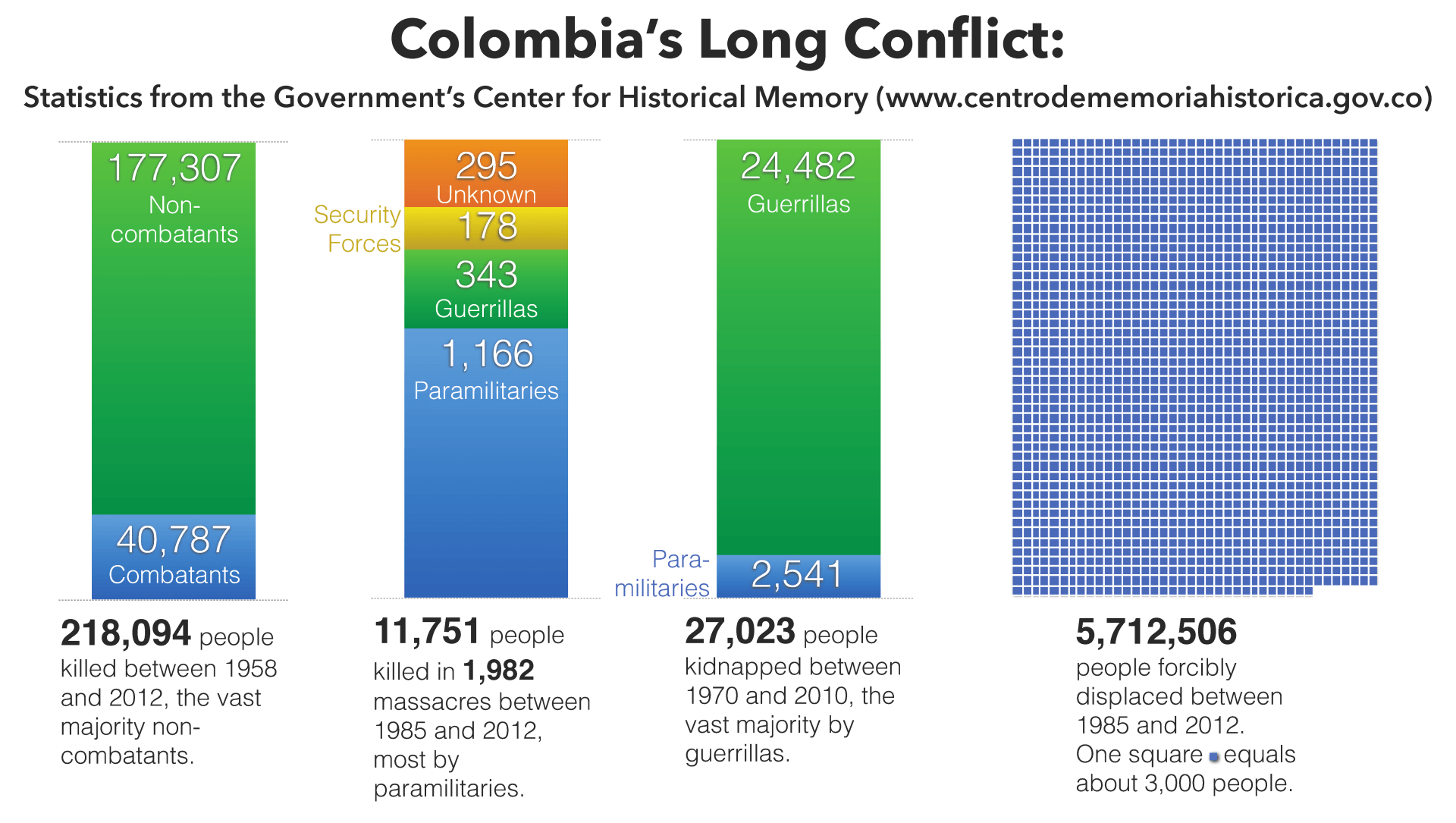

In the 20th century Colombia has also suffered a great deal of violence, caused by a civil war between the government, guerrilla militias, paramilitaries, the infamous drug cartels, and several foreign actors, such as the US government and multinational corporations. This background story is not the place for a complete analysis of the violence in Colombia and the responsibilities of each party. However, it is important to look at what has been labelled as the solution of a situation that was once deemed unresolvable.

In 2000, U.S. president Bill Clinton authorized “Plan Colombia”, “a $1.3 billion U.S. package for the war on drugs with military assistance that included helicopters, planes, and training, a massive chemical and biological warfare effort, and electronic surveillance technology” (Villar & Cottle, 2011: 107). Since Plan Colombia, the U.S. has invested approximately $500 million annually in assistance to Colombia (USAID, 2013), leaving a total of $9.3 billion from 2002 to 2014 (Isacson, 2014).

Officially, Plan Colombia was motivated to stop the flood of cocaine on the U.S. market (Villar & Cottle, 2011: 107). However, several have argued that the real focus of Plan Colombia was the growing threat of the left-wing guerrilla militia called the FARC (Ibid.). For instance, one of the tactics of Plan Colombia was to attack coca fields with biochemical agents, which had devastating consequences on the environment (Ibid: 129). However, only areas controlled by the FARC have been targeted by these agents (Ibid.). And despite this war on drugs, the drug industry still generates an annual profit of almost $9 billion USD (Højen, 2015). A 2018 UN report showed that in 2017 cocaine production was at an all-time high (UN, 2018). Looking at the statistics, the war on drugs “has neither reduced the amount of coca grown nor the cocaine exported” (Villar & Cottle, 2011: 177).

Furthermore, alongside Plan Colombia, Colombian governments have adopted neoliberal policies that have further integrated Colombia into the global economy (Maher, 2018: 71). “President Uribe supported the introduction of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) structural adjustment programs, privatization, and Colombia’s membership in the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA)” (Villar & Cottle, 2011: 110). “Neoliberal policies had a profound impact on the Colombian economy and social structure, creating a powerful transnational class of businessmen and investors” (Ibid: 111). These policies have made Colombia more attractive for foreign investment (Maher, 2018: 95) and caused an enormous influx of multinational countries into the country.

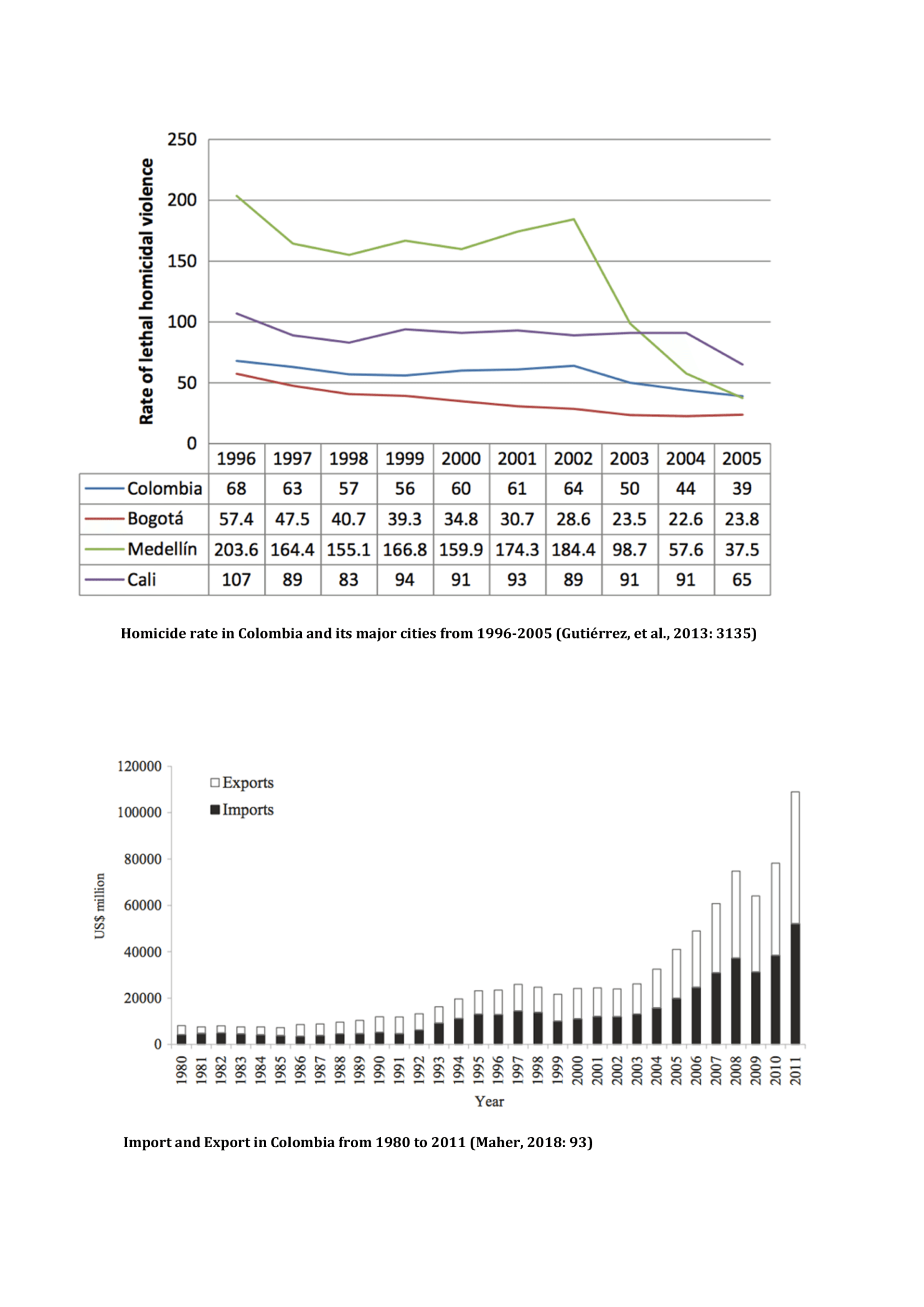

Alongside the neoliberal policies, security expenses have also increased in Colombia, creating a more business friendly environment (Maher, 2018: 95). According to the World Bank this has led to a reduction of violence all over the country (Ibid.). Indeed, numbers show a general decline of violence (Gutiérrez, et al., 2013: 3135). As is shown in the graph above, especially the city of Medellín that was once dubbed “the most dangerous city in the world” has experienced a massive transformation, as its homicide rate is now below the country’s average.

These statistics confirm the analysis of the Lonely Planet cited in the beginning of this article: Colombia has overcome its violent past and is now one of the most thriving and fastest growing economies in Latin America. In 2016 the FARC and the Colombian government reached a peace agreement, ending the longest armed insurgency in Latin America (Gigova & Quiñones, 2016). President Juan Manuel Santos even received The Nobel Peace Prize "for his resolute efforts to bring the country's more than 50-year-long civil war to an end" (nobelprize.org). The graph below shows the legacy of the conflict.

"Safe for Business, not for people"

However this doesn’t mean all trouble is in the past. Gutiérrez et al. point out that, while violence in Colombia has seen a major decline, poverty and inequality have not declined (2013: 3146). In contrast, while the general safety was increasing, levels of poverty and inequality have actually risen (Aviles, 2006: 90). Moreover, human rights lawyer Dan Kovalik explains, “the murder of social, political and human rights activists is actually increasing in Colombia” (2017). In fact, more than a 1.000 community organizers and activists have been murdered since the accords were signed in November 2016. Diaz and Jiménez believe that most of these deaths and death threats can be traced back to paramilitaries that haven’t been dismantled during Colombia’s peace progress (2018).

There have been some cases that transnational corporations have directly paid paramilitary armies to protect their business activities. For instance, the Swiss banana company Chiquita,

“pled guilty to paying the paramilitary groups 1.7 million dollars over a 7-year period, between 1997 and 2004, and giving them 3.000 Kalashnikov rifles. (…) Thousands of people were killed by the paramilitaries that Chiquita paid” (Vaz, 2017).

Chiquita was only fined 25 million dollars and continues to produce bananas in Colombia (Ibid.). Furthermore, between 1996 and 2006, paramilitaries were responsible for the murder of 3.100 people and the displacement of 55.000 people in the mining region of Colombia (Het Parool, 2016). Paramilitaries have testified they were paid by mining companies, who provide coals that warm many western households, including major Dutch energy distributors such as Nuon and Essent, thus linking “Amsterdam’s electricity consumption to the killings of poor Colombians” (Ibid.).

Displacement is another major issue in Colombia. As a result of Colombia’s conflict there are more than 7,7 million internally displaced people in Colombia (UNHCR, 2016). After Syria, this is the highest number in the world. Many displaced people move to the major cities only to live in extreme poverty, and without any social security. Louise Højen calls it Colombia’s ‘Invisible Crisis’, it being one of the major threats to its basic development in the near future (2015).

And indeed since the administration of current president Ivan Duque, the war has been reignited, as many former militants are unhappy with how the government has kept up their promises of the 2016 peace agreement.

Aviles concludes that the political and economic reforms of the last decades have resulted in the institution of

“a new form of elite rule concomitant with the requirements of capitalist globalization, in which the internal role of the armed forces remains prominent, economic inequality and deprivation remain as continuing challenges, and the democratic behavior of states are conditioned by transnational interests” (Aviles, 2006: 147).

While Colombia has gone through major transformations since the days of Pablo Escobar and the heyday of the conflict, Maher emphasizes: “When it is said that security has increased in Colombia, one must ask the question: Security for whom?” (2018: 96). The headline of an article by Ricardo Vaz, states a clear answer: “Colombia is safe for business, but not for people” (2017).