Global Suffering

We live in a world where many are suffering

Violence, poverty, climate change and racism are just a few of the factors causing millions of people to live in despair. Currently, As of 2020, 91,9 million people are (officially) displaced from their homes due to violence, hunger or natural disasters (UNHCR, 2020). 11,2 million of them currently reside in Colombia (Ibid.). Millions more are forced to stay in those circumstances for they have nowhere else to go.

Living in these circumstances causes a whole range of new problems, adding to their already unimaginable amounts of suffering. Some have seen loved-ones die, moms and dads blown-up by foreign bombs, sons starved to death and daughters raped in front of their eyes. Leaving behind everything and everyone they love, exiled from their homes and strangers to their destinations, they now face discrimination, racism and stigmatization. Struggling day in a day out just to get some food on the table they are treated as criminals because of their skin color, descent or social status. Denied of papers, education and healthcare many are exploited by gangs and companies that use their desperation for their own benefit. Being reminded over and over again of their worthlessness and accused over and over again of crimes they didn’t commit, the point comes at which some start to believe those lies themselves. Feeling no better than a criminal they either accept their faith or find escape through self-harm. Consequently, one can imagine the psychological damages these circumstances may cause, pushing them into a downward spiral that can only end in drug addiction, jail or death; another live destroyed, another life wasted, another life’s potential unfulfilled.

But we also know that it’s those who have suffered the most, are the ones who have inspired us the most. Nelson Mandela spend 27 years in prison before he ended formal apartheid in South Africa. Malcom X lost his father to racist murderers, became a drug addicted criminal, serving 9 years in jail, before he became one of the most influential civil rights activists in the world to this day. About his own life he noted:

“I believe that it would be almost impossible to find anywhere in America a black man who has lived further down in the mud of human society than I have; or a black man who has been any more ignorant than I have been; or a black man who has suffered more anguish during his life than I have. But it is only after the deepest darkness that the greatest light can come; it is only after the extreme grief that the greatest joy can come; it is only after slavery and prison that the sweetest appreciation of freedom can come” (Malcom X, 2007: 498).

Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, an Auschwitz concentration camp survivor, explains why suffering is not just an evil to avoid, but it is part of the meaning of life:

“There are situations in which one is cut off from the opportunity to do one’s work or to enjoy one’s life; but what never can be ruled out is the unavoidability of suffering. In accepting this challenge to suffer bravely, life has a meaning up until the last moment, and it retains this meaning literally to the end. In other words, life’s meaning is an unconditional one, for it even includes the potential meaning of unavoidable suffering” (Frankl, 2008: 118).

In other words, when suffering is given an objective, or meaning, it can be turned into something positive, turning the downward spiral upward, towards a life of happiness and fulfilment. This the point from which we depart. We see all the suffering in the world and rather than running away from it, we look it right in the eye and use it to empower, grow and succeed. “The Buddha called suffering a Holy Truth, because our suffering has the capacity of showing us the path to liberation” (Nhat Hanh, 1998: 5). To find this path we need to have a more profound understanding of the world’s suffering. The following therefore describes how we understand the mechanisms of suffering in this world. This is the basis on which Upeksha builds its vision, mission and activities.

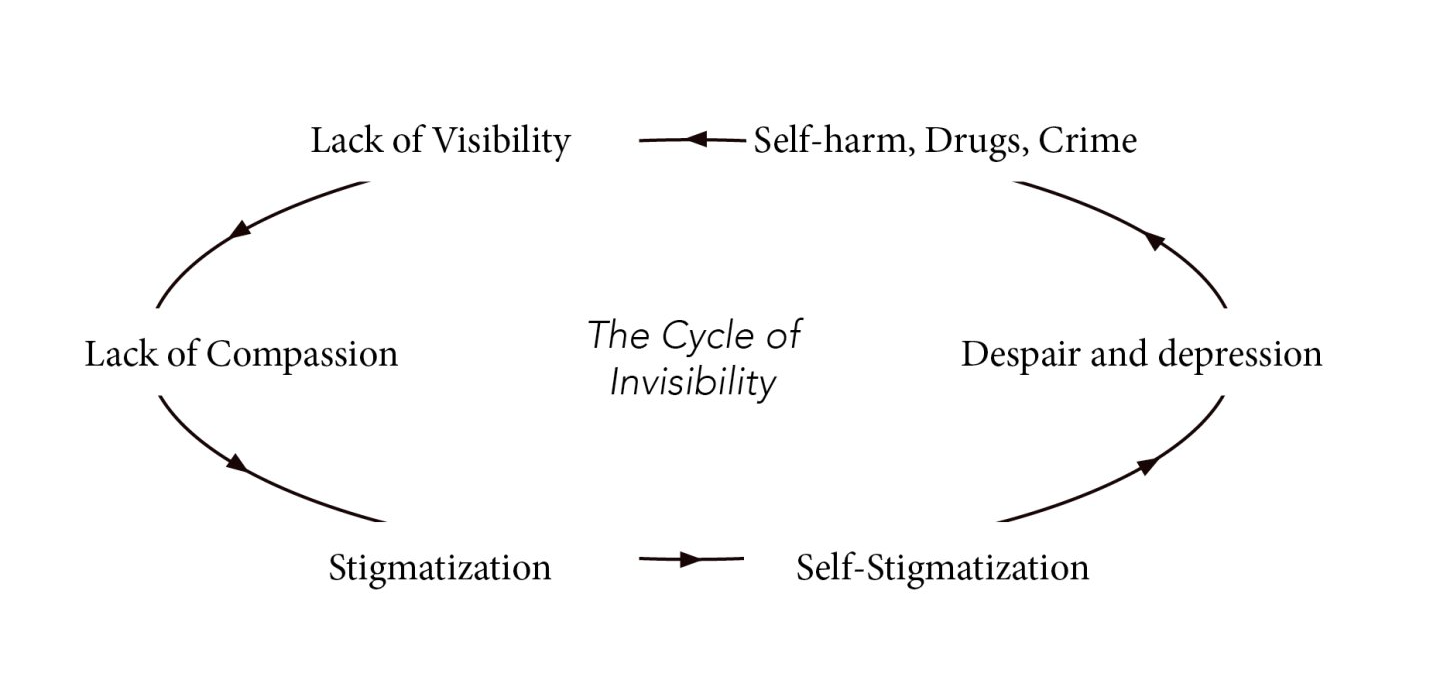

The Cycle of Invisibility

Since we are children, we are afraid of the dark. We are afraid of what we cannot see and until we look, we imagine monsters living under our bed and ghosts in our closets. The same happens with marginalized groups of people such as refugees, homeless people and slumdwellers. Their marginalized position in society keeps them from being seen, allowing others to create ghost stories, turning them into monsters such as criminals, rapists or terrorists. Because of this image we put them in camps, prisons, and we let them drown in the ocean. We don’t really feel bad about this because who feels bad about a terrorist? Upeksha considers this the very reason of much of the suffering in the world. The lack of visibility of people in need causes a lack of compassion and empathy. Because we cannot see them, we create ghost stories out of fear. We stigmatize people, create stereotypes and discriminate, only to increase the suffering of those that already suffer. While these very people, more often than not, seem to show human resilience beyond our imagination, at some point a limit will be reached. Many of us know what it is like to be bullied in school. You are hurt, you feel bad about yourself and you start to think whether it might be true what they say. Now imagine an entire society bullies you. At some point people will start self-stigmatizing and this is will lead to further psychological problems like depression and despair. Imagine living in a society where opportunities for a better life are scarce, while many people around you bully you for your skin colour or your heritage, and on top of that you have no faith in yourself and your future. This will lead harmful actions. Sometimes towards others, more often towards oneself. These actions will only put you further into the darkness and the cycle starts all over again. We call it the cycle of invisibility because all of this could have just been prevented by listening. At the same time, it is well-known that those at the margins of society very rarely have to opportunity to tell their story. Being at the “margins of society” can be caused by anything from poverty to displacement and from addiction to mental sickness. Eduardo Galeano describes:

“The prevailing social order perverts or annihilates the creative capacity of the immense majority of people and reduces the possibility of creation – an age-old response to human anguish and the certainty of death–to its professional exercise by a handful of specialists” (Galeano, 1992: 133).

The refugee, the homeless person, the slum-dweller, what do we really know about them? Think about it. You may have heard about them quit often, but how often did you hear them tell their story? Other people will fill that void with their own stories. It creates a cycle that needs to be broken and that is exactly what Upeksha aspires to do. Therefore, Upeksha aims to provide a space where voices that historically have been ignored and silenced can be heard. Upeksha aims to disprove those ghost stories by co-creating spaces with those living in the darkness, to show the world who they really are, to create a mutual understanding that leads to compassion rather than fear, to solidarity rather than violence, and love rather than hate.

| The Cycle Of Invisibility | Breaking the Cycle |

|---|---|

| Lack of Visibility | Co-create Spaces for voices to be heard |

| Lack of Compassion and Empathy | Indiscriminate Compassion and Empathy |

| Dehumanization/Discrimination/Stigmatization | Upeksha – Indiscriminate Love |

| Self-stigmatization and self-doubt | Self-Love and believe |

| Despair and Depression | Self-fulfillment |

| Self-Harm, Drugs and Crime | Society of compassion, equality and love |

Social Suffering

How change happens

For instance, Antonio Gramsci argued that power is often not exercised through coercion, but rather through consent:

“State power relies more upon subtle mechanisms of ideological integration, cultural influence or even psychological dependency” (Thomas, 2013: 21).

Michel Foucault explains further: with this kind of power

“there is no need for arms, physical violence, material constraints. A superb formula: power exercised continuously and for what turns out to be at minimal cost” (1980: 155).

One particular important manifestation of invisible power is the creation of stereotypes, in which people start making assumptions and predictions of other people’s behaviours, based on their perception of them as a race, class, religious group, or other. Psychologists Fiske et al. explain that psychological research has established that stereotypes are captured by two dimensions: perceived warmth and competence (2002: 878). Discriminating behaviour and actions towards particular groups is legitimized by a lack of either one of these dimensions (Ibid: 879). Fiske et al. point out that these groups often include the poor, homeless people, ethnic minorities, drug addicts and undocumented migrants (2007: 80). But it really applies to anyone that doesn’t fit in with what is generally considered “normal”. When people internalize stereotypes of these people, it has consequences for the behaviour towards them (Ibid: 81). A perception of warmth and competence, Fiske et al. explain, produces active (helping) and passive (association) facilitation of the warm and competent group, while actively (attacking) and passively (neglecting) harming the unwarm and incompetent group (Ibid.). Besides behaviours, stereotypes also produce feelings which can legitimize those behaviours: contempt and pity for the unwarm and incompetent, admiration and envy for the warm and competent (Ibid.). This explains how invisibility causes the creation of stereotypes which further pushes people down the spiral. These behavioural and emotional consequences will reproduce inequality and could legitimize forms of exclusion or repression, as world war II has shown us in the most extreme way.

Social psychologists have posed and proven the theory that prejudice is largely related with a lack of contact between groups. Intergroup contact has been shown to decrease prejudice by decreasing fear for the other group and inducing empathy (Pettigrew, 2017: 110). Pettigrew and Tropp have pointed out that not only do the attitudes towards the other become more favorable between direct participants, but so do the attitudes towards the entire outgroup (2006: 766). Connecting people thus becomes an important tool to counter discrimination and hate.

However, it is important to understand that these stereotypes don’t just come out of nowhere. Pettigrew points out that “authoritarian leaders have long understood they can attract followers by enhancing the perception of dangerous threats to the society and offering simple solutions” (2017: 112). Or as George Orwell put it:

“Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind” (2004: 120).

Therefore stereotypes are sometimes actively manufactured by the powerful to push a certain agenda or to legitimize actions that may otherwise sound criminal. This is conceptualized in what Green calls “hidden power” (2016: 30). Green argues, “discussion of the facts usually takes place parallel to a shadowy world of competing narratives that have little basis or interest in evidence” (Ibid.). Eduardo Galeano poetically writes how the narratives of the powerful are the ones that find their way into the history books and newspapers, while those of the poor get lost:

“Official history, mutilated memory, is a long, self-serving ceremony for those who give the orders in this world. Their spotlights illuminate the heights and leave the grass roots in darkness. The always invisible are at best props on the stage of history” (1998: 509).

The made-up stories about refugees, homeless people and slum-dwellers usually contribute to this image of un-warmth and incompetence. They are often described as violent, uneducated and immoral. These images, these stereotypes, even though they are false, have very true consequences. They legitimize violence, imprisonment and human right violations against these people. In World War II we have seen the worst of this phenomena, but we have to be very aware of the presence of such injustices in our present-day world. Children are drowning in European waters, murdered by the police in the United States and by state-backed paramilitaries in Colombia. All of this happens more often than not without any consequences, as a result of those stereotypes. Fighting those stereotypes therefore lies at the basis of bringing justice upon the world.

Learning to Love

“Please don’t be scared of us. We are more terrified of your reactions. We are broken people who are haunted by our past, our future and our dreams. We narrowly escaped death, the war, the rapes, the murders and the killers–we have family who didn’t–please don’t think those monsters represent us. We swam through our country’s blood barely keeping our heads afloat to breathe, to survive and to live another day. We left our homes, we left our history. We left our loved ones without the time to mourn them. We brought our hearts, but they have been shattered into tiny pieces. We didn’t come here to harm you, we’ve come to heal”. (Abawi, 2018: 269).

We know the harm stereotypes can do. My great aunt Corrie ten Boom knows all about this, as she and her sister were sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp in World War II. While in the camp, Corrie’s sister Bettie, said:

“Corrie, if people can be taught to hate, they can be taught to love! We must find the way, you and I, no matter how long it takes…” (Ten Boom, 1971: 164).

Two days later Bettie would die. But her words hold a truth important for us to remember. In the middle of the atrocities of Nazi Germany, knowing she would probably die at the hands of those guards that treated her in ways we cannot even dare to imagine, she was strong enough to remember that this hate is not something intrinsic to human nature. Hate is taught, and so it can be untaught. Where Bettie wasn’t able to put her words to action, Upeksha will take up her wisdom and do everything to unteach hate and to replace it with indiscriminate love. In order to love everybody without any discrimination it is important that we understand each other as human beings. We can only have compassion and empathy when we have understanding. Therefore, to help those who are suffering we need to understand their suffering deeply and compassionately. The next part examines the psychological injuries that might exist in people as a result of atrocities such as violence, war, poverty, displacement, disease, loss of freedom, discrimination and hate.

Psychological Suffering

To create a broad and inclusive society

it is necessary to heal the wounds within us, to value ourselves, to forgive, and to recognize others. Some years ago, the first conversation we shared, long before we knew that our passions would be brought together and translated into this NGO, we discussed the importance of healing our soul before our pain becomes something else. How would the world look if presidents came to power after forgiving those who hurt them, after healing their childhood wounds, after learning to recognize their emotions and where they came from? We figured that if they healed, they would not pay for wars, they would not propagate hate and division. They would be compassionate, empathetic, and loving. And what if it were not just the presidents who healed, but society as a whole? We could love without borders, without hate, without fear. We would be the community we dream of, with equal, inclusive, compassionate, caring, and loving human beings.

It is essential to understand PTSD, depression, and anxiety, being the most common mental disorders caused by traumatic and stressful experiences lived by those who have gone through forced-displacement, violence, war, poverty, and other atrocities.

PTSD is a term that first appeared in WWI by the name of ‘Shell shock’. It was first used to describe the mental aftermath of veterans as a reaction to what they experienced during the war. Later studies showed this syndrome not only appears in soldiers or war survivors, but can appear in anyone who experienced any kind of traumatic event. The main characteristic of PTSD is that its symptoms can prevail long after the traumatic event has ended. The main symptoms (not the only ones) are distressing thoughts and flashbacks, blocking the event from the memory, negative thoughts, emotional reactivity, and negative judgment regarding the future (Crocq & Crocq, 2000).

Depression is a mental disorder that has symptoms such as a permanent or constant feeling of sadness, loss of interest, hopelessness, change in sleeping patterns and slow cognitive abilities. While everybody has these symptoms once in a while, the constant presence of them to the extent it interferes with a person's life structure, is what makes it pathological. Depression can be connected to the experience of a traumatic event, although it can also be a product of the environment and heritage of the individual (Paykel, 2008).

Lastly, pathological anxiety disorder is the constantly present feeling of anxiousness and worry (Lambert & Baruch, 2007). With this disorder, a person’s thoughts often revolve around fatality and tragedy, and the perceived future is uncertain and negative. The constant worry of a time yet to be lived interferes with the daily activities of the present. This disorder not only affects daily activities but also has a negative effect on self-worth, self-perspective, and the ability to make decisions (Ibid.).

These three concepts are essential in understanding why a psychological approach is so important for the work with marginalized populations. The living situations combined with social marginalization and the perpetuation of a negative imagine created through stereotypes and cultural segregation creates physical and mental states of constant tension, hopelessness, self-doubt, anxiety and depression. This state of mind makes it almost impossible for these people to enter and contribute to society. That is why it is essential to co-create spaces of creation, resignification and reconstruction, not only of the individual but of society as a whole. This space seeks to give us the opportunity to see ourselves from within, to know what is wrong but more than anything else, it helps us know what talents and abilities we have, so we can build a future that we do not fear but rather yearn for.

Upeksha has chosen to use a non-conventional treatment methods. First, we see the need for a less invasive and more internalized and self-reflective intervention, as it can often be difficult for people to look their pain straight in the eye. Art, for example, has the ability to externalize an event where the person can observe the experience objectively and reflect on it without judgment. Sociologist Vianne argues that conventional Western treatment has little understanding of alternative medicine, including art, music, dance, meditation and yoga. She stressed that understanding one's culture is an essential part of healing. It is therefore necessary to approach communities in their own language. For example, Latin American and Eastern communities approach the psyche in a more spiritual way than what is common in Western medicine. Upeksha therefore adapts its projects to cultural and individual needs. We believe that healing can ultimately only come from within and the method of healing should therefore be as close to the heart as possible.